On May 1, 1886

The 1st May Day Demonstration

took place in Chicago

at the time, there was a growing movement of socialists, communists, anarchists

Cell 29

A historical play (edited and abridged) incorporating the actual writings and speeches of the principal characters – performed annually at the May 1st meeting of the College of Complexes

“The time will come when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you are strangling today! Here you will tread upon a spark, and here and there, and behind you and in front of you and everywhere the flames will blaze up! You cannot put it out. The ground is on fire upon which you stand!”

May Day was born and raised in the streets of Chicago

Chicago Reader, by Miles Kampf-Lassin May 1, 2017

On Monday, May 1, hundreds of thousands of immigrants, activists, and workers of all stripes are expected to take to the streets in cities across the country and the globe to commemorate International Workers' Day, aka May Day.

Here in Chicago, a massive rally and march are planned, starting in Union Park at 1 PM and then snaking throughout downtown and the West Loop.

This year, facing the unique threats the Trump administration poses to working people everywhere—and immigrant communities particularly—a patchwork of organizations have coalesced to help organize what are likely to be the largest May Day demonstrations in more than a decade. And participants won't just be rallying and marching—many will be striking, withholding their labor to show their collective power.

But whether or not you plan to take part in the protests, you can take heart in the central role Chicago has played in May Day's history: its roots were planted right here on the shores of Lake Michigan.

May Day's origins are centered around the call for an eight-hour workday, a fact of life many of us take for granted but which was fought for fiercely by industrial workers facing brutal conditions in the late 19th century. And it was in Chicago, then a rapidly industrializing city, that these calls reached a fever pitch in 1886, resulting in the violent tragedy of the Haymarket Massacre.

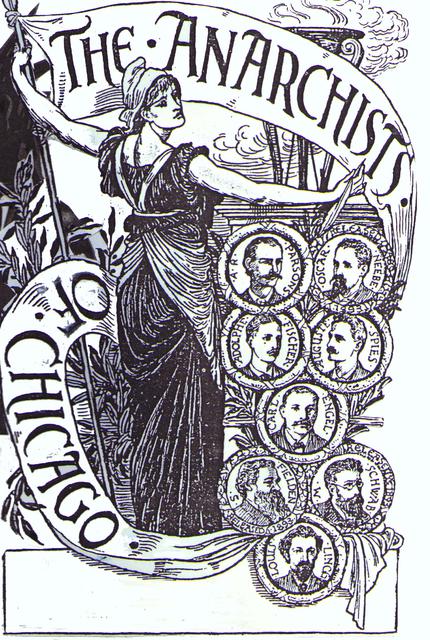

At the time, a growing movement of socialists, communists, anarchists, and labor unions was sweeping the country, provoked in large part by the horrendous standards of living that were the reality for large swaths of the population, especially African-Americans, immigrants, and the poor.

Federations of workers organized in large numbers, forming such groups as the Noble Order of the Knights of Labor and the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions (FOTLU), which later became the American Federation of Labor.

In Chicago, the massive influx of immigrants from Europe, along with rising income inequality and the dramatic and dangerous effects of unbridled industrialization as documented in Upton Sinclair's classic book The Jungle, contributed to monumental unrest in the city.

Working conditions in urban centers across the country were by and large unsafe and unsanitary, and workers were commonly kept on the job from 12 to 18 hours a day. The resulting health effects were devastating, compounded by the crowded and disease-ridden conditions of tenements and ghettos in which urban workers were forced to live.

Under these conditions the radical views of socialist and anarchist groups began to spread throughout American cities, offering more democratic and humane visions of how society could be organized.

In this sense, the calls for an eight-hour workday were truly radical, inverting the relationship workers had to their employers by demanding not only less time on the job, but also the right to self-determination and the ability to set the standards for how their lives were organized. A common slogan of what became known as the Eight-Hour Movement was "Eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, eight hours for what we will."

Chicago was on the front lines of this movement. Agitation by workers' groups led to the passage of the first statewide eight-hour workday law in Illinois in 1867. But when the law was set to go into effect on May 1 of that year, employers disregarded the regulation, leading to the first general strike in Chicago in support of the eight-hour workday.

The struggle for enforcement of the law continued to grow over the following years, as did radicalization amongst the city's largely immigrant working class. Radical publications sprouted up, including the German anarchist newspaper Chicagoer Arbeiter-Zeitung and pioneer American socialist Albert Parsons's The Alarm. In a manifesto written at the Pittsburgh Congress of the International Working People's Association in 1883, the "Chicago Idea" was first presented, proclaiming: "Agitation for the purpose of organization; organization for the purpose of rebellion. In these few words the ways are marked which workers must take if they want to be rid of their chains."

In 1884, the FOTLU held its national conference in Chicago, affirming that "eight hours shall constitute a legal day's labor from and after May 1, 1886." A popular pamphlet that circulated throughout working-class communities in 1885 called for "One day of revolt—not rest! A day on which labor makes its own laws and has the power to execute them! All without the consent or approval of those who oppress and rule. . . . A day on which to begin to enjoy 'eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, eight hours for what we will.'"

These proclamations set the stage for the massive strikes that would engulf the nation on that historic date. More than 35,000 people walked off the job and marched through the streets of Chicago on what is now known as the first May Day demonstration, part of a nationwide general strike that saw more than 300,000 participants.

Along with demanding an eight-hour workday, the groups involved animated the demonstrations with calls for participatory politics and a more equal economy, challenging the deep-seated class stratification that marked American society at the time.

Although the May Day general strike was generally peaceful, two days later things took a violent turn at the McCormick Reaper Works factory, where police clashed with strikers, leaving two dead and many more injured.

The next day, May 4, 1886, a public meeting was held at Haymarket Square, where roughly 3,000 people converged. A number of speakers including Parsons and radical labor activist August Spies addressed the crowd under a light but steady rain.

As the speeches wrapped up, a large group of police moved in to disperse the meeting. During the commotion, an unidentified individual threw a bomb into the crowd. Officers began to fire indiscriminately. What is now known as the Haymarket Massacre left at least 12 dead, though the exact number of casualties among demonstrators is still unknown.

The red scare and activist witch hunt that followed did great damage to the labor movement in the United States, and led to Parsons, Spies, and other agitators being hung from the gallows. But in many ways the Haymarket tragedy also set the grounds for May 1 as a worldwide day of action for workers' rights.

In 1888, the American Federation of Labor (formerly the FOTLU) called another general strike on May 1, 1890, to again demand an eight-hour workday. After receiving a letter from AFL president Samuel Gompers, the Second International of the world's Socialists meeting in Paris in 1889 backed the call, designating May 1 as a universal international workers' day, citing the legacy of the Haymarket Massacre.

That first international May Day of 1890 saw demonstrations spanning the globe, from more than two dozen European cities to Peru, Chile, and Cuba.

While it took until the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1937 for the eight-hour workday to be legislated on a national level in the United States, the dedicated organizing and activism that marked the early May Day protests were integral to making this demand a reality.

Chicago played a fundamental role in this transformation, and in establishing the tradition of May Day as a global day of protest to demand justice, equality, and workers' rights as well as a fairer economy.

The tradition was continued in Chicago in 2006, when more than 500,000 took to the streets demanding rights for immigrants and undocumented workers in one of the largest demonstrations in the city's modern history.

This year's rally and march have been endorsed by 126 organizations across the city, including the Chicago Teachers Union, Black Youth Project 100, the Chicago Democratic Socialists of America, the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights, and many others.

So whether you'll be marching, striking, or working an eight-hour shift, this May Day is an opportunity to reflect on the vital role this city has played in improving the lives of working people of all backgrounds—a calling ever more important in Trump's America.